Odds are, if your curiosity draws from the realm of Georgia's native plants, wildlife, or natural history, you are likely to have noticed the many ferns living among us. While admiring these mysterious, prehistoric plants, you may have found yourself wanting to know more about their unique lifestyles and how they came to be so common. Today, we hope to indulge your curiosity and encourage you to enjoy the process of growing them for yourselves.

This post will guide you through a brief history of how ferns came into existence millions of years ago, and includes a lesson on basic fern biology, with a peek into their fascinating reproductive cycles. Hopefully, you`ll see these amazing plants the way we do, with total admiration and awe!

Ferns (Polypodiopsida), along with their pioneering relatives – liverworts (marchantiophytes) and clubmosses (lycophytes) – were some of the first plants on land. They have been around for over 350 million years, dating back to the Devonian era (also known as the “Age of Fishes”). Around that time, the first forests appeared, and early tetrapods began to crawl onto land.

At this time, the Earth was much warmer, and the overall climate was relatively stable throughout, which allowed for the earliest land plants to take root and spread. Since then, the Earth has undergone multiple geographical (tectonic activity) and climatic changes (glaciations). These changes led to a change in growing conditions, resulting in the extinction of many species of fern.

The ferns commonly seen today represent a very narrow scope of sizes, shapes, and textures. Some early – now extinct – ferns include the Pseudosporochnales, which grew as tall as trees, and the Stauropterids, which were reminiscent of small, feathery shrubs. The earliest ferns evolved and proliferated in wetlands, which covered a significant part of the prehistoric supercontinents. In-fact, most of the coal and oil reserves we have today are the result of the rampant growth – and decay – of these early fern species. As the ferns died, the plant material would sink into oxygen-devoid swamps. These anoxic conditions prevented micro-organisms from breaking down the plant tissues, so with time (and a lot of pressure), the plant material became fossilized – hence the name “fossil fuels”.

Today, there are over 10,000 species of fern. Georgia is home to 119 species (along with some hybrid species), which inhabit a multitude of habitat types stretching from the Coastal Plain to the Blue Ridge. Ferns are commonly found in early successional plant communities (see our last blog post for more about succession).

Ferns grow by taking root in bogs, rock-crevices, marshes, coves, and other warm, moist areas. Some ferns even grow epiphytically (on trees). Generally speaking, ferns are ill adapted to cold climates and high altitudes, so it is uncommon to find them outside of the tropical, subtropical, and temperate zones.

We’ve been dancing around the question: “What makes ferns so successful that they’ve outlived millions of years of global change?” The answer comes down to their biological simplicity and a little bit of luck. Ferns have evolved on the same playing field as all other organisms through geologic time, meaning they have been able to survive, adapt, and persist today. These “living fossils” (again, it is important to note that they have continued to evolve over time) have a unique reproductive mechanism, dating back to a time before gymnosperms and flowering plants (angiosperms) became the dominant flora. Blend a consistently warm climate with rich soil and bit of water: there you have a perfect place for ferns to thrive.

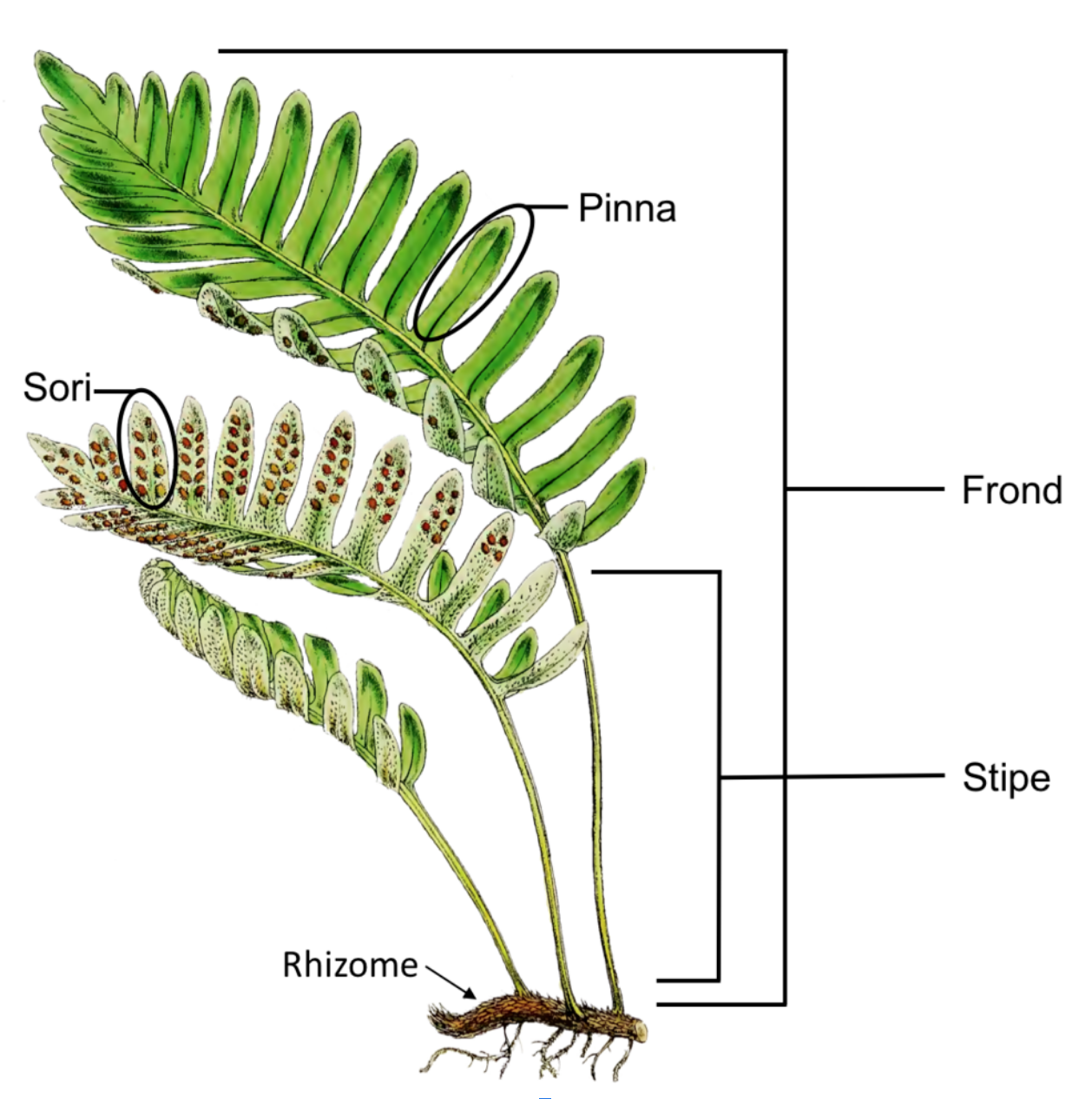

Before we dive into fern reproduction, you`ll need to familiarize yourself with their important parts. Ferns (and other vascular plants) have a true root system, simple stems, and leaves. The key difference between ferns and other vascular plants is that ferns reproduce via dust-like spores, which are commonly found along the backsides of the leaves (pinnae).

The rhizome functions to absorb water and anchors the stalk (stipe) to the soil. Branching from the stalk are the individual leaves (singular: pinna).

(note: Permission to use this beautiful illustration of fern anatomy has been granted by the American Fern Society. Visit their website here.)

Together, the stalk and its leaves form a frond. Fern leaves can have highly complex arrangements, with leaflets arising from leaflets arising from leaflets, making identification tricky. We’ve included some useful websites for identifying ferns and selecting native ferns for your landscape. Please refer to the “Additional Resources” below.

Additional Resources

- A wonderful resource worth diving into: American Fern Society- https://www.amerfernsoc.org/

- "Ferns That Work For You" by Ellen Honeycutt: http://usinggeorgianativeplants.blogspot.com/2012/05/ferns-that-work-for-you.html

- UGA Publication on growing ferns in Georgia: https://secure.caes.uga.edu/extension/publications/files/pdf/B%20987-2_7.PDF

- For Fern Identification: Weakley`s Flora of the Southeastern U.S. 2022- http://www.herbarium.unc.edu/flora.htm