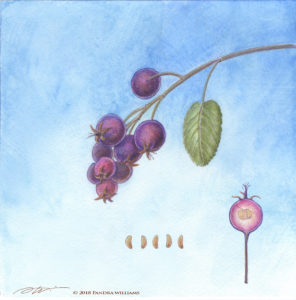

Call it a Juneberry, Serviceberry, Shadbush, Sarvisberry, or Saskatoon; the Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp) is a native tree that occurs throughout North America. Roughly 14 different species species range from the East to West coasts, and from the northern tip of Alaska down across Canada into the southern reach of Texas.

Currently, Serviceberry is a very popular blog topic, for a lot of good reasons. A member of the rose family, it’s smothered in beautiful white flowers in the spring. Naturally a small tree, with large berries that are dark blue to purple when ripe, it’s perfect for an edible landscape in either sun or part shade. As a tasty and nutritious fruit packed with anthocyanins and vitamins, it’s got all the right healthy talking points. Beyond all the recent chatter found online, this small fruit tree has a long, deep history with both the early people of North America and the Western explorers and Colonists.

As I was rooting around in the Congressional Archive and the internet for cultural history on the uses of Serviceberry, references to pemikan (also spelled pemmican) kept popping up. Containing 50% dried, pulverized meat, 20% soft tallow, 20% hard tallow, pemikan often had 10% dried berries added into the mix, if they were available. The berry I found mentioned most frequently in historical pemikan recipes was the Serviceberry.

One of the reasons most often cited for adding berries to pemikan was as a flavoring. Consider a cold dark winter, with not much fresh food available, dietary protein and fat needs would be taken care of by the meat and tallow, but Vitamins A, B complex, and C, bioflavinoids, anthocyanins and fiber would be more plentiful in fruits and veggies. In addition, the Serviceberry fruit contains protein as well, so it’s not surprising that this berry was an important food. Bountiful Serviceberry harvests would be either dried and stored as loose berries, or mashed into flat cakes and stored for lean times.

For the First Peoples of the North American Plains, storing enough pemikan and dried Serviceberry, along with other dried berries and roots, could be a matter of life and death in a land where winters were long and winter food was scarce. In warmer seasons, animals such as buffalo and elk were more likely to be in the open prairies and meadows eating tender grasses and flowering herbs, making clearer targets for hunters. During the winter, with animals sheltering in woody thickets, hunting was more difficult. Pemikan was a way to preserve meat for months, or even years, after a season of successful hunts. If a tribe’s cache of pemikan ran out, they survived on their winter stores of dried fruits and roots.

For the First Peoples of the North American Plains, storing enough pemikan and dried Serviceberry, along with other dried berries and roots, could be a matter of life and death in a land where winters were long and winter food was scarce. In warmer seasons, animals such as buffalo and elk were more likely to be in the open prairies and meadows eating tender grasses and flowering herbs, making clearer targets for hunters. During the winter, with animals sheltering in woody thickets, hunting was more difficult. Pemikan was a way to preserve meat for months, or even years, after a season of successful hunts. If a tribe’s cache of pemikan ran out, they survived on their winter stores of dried fruits and roots.

In summer months, when Serviceberries ripened in June, both Colonists and First Peoples ate them fresh off of the tree. Colonists had plenty of their own Western style summer recipes for serviceberries, including preserves, tarts and pies. If we wander back into the culinary delights of the 21st Century, the internet is full of Serviceberry recipes in pies, jellies, jams, compotes, scones, galettes, and beer.

If all that berry history and berry goodness doesn’t tempt you into planting your very own Saskatoon/Serviceberry in your native garden, perhaps a butterfly-in-your-habitat-garden reason will: Serviceberry is a larval host plant for the Red-spotted Purple Butterfly or White Admiral Butterfly, Limenitis arthemis. Limenitis arthemis comes in two color forms: The White Admiral of the northern USA through Canada, and the Red Spotted Purple, which is the color form of this butterfly in the southern USA. The Red Spotted Purple color form mimics the bad tasting Pipevine Swallowtail butterfly (Battus philenor) to fend off hungry birds.

The Red Spotted Purple frequently uses many trees in the southern United States from the

Red Spotted Purple adults feed/nectar on small white flowers, sap flows, and rotting fruit, even dung. It should be easy to host the adults in a native perennial garden, once a larval host tree or two is in place in the garden. We have several Serviceberry Trees planted at Beech Hollow, but after writing this post, I think it’s time I planted a couple in my yard…

More on the Red Spotted Purple or White Admiral Butterfly here.

More on wild edibles here, and here

More on habitat gardening here.