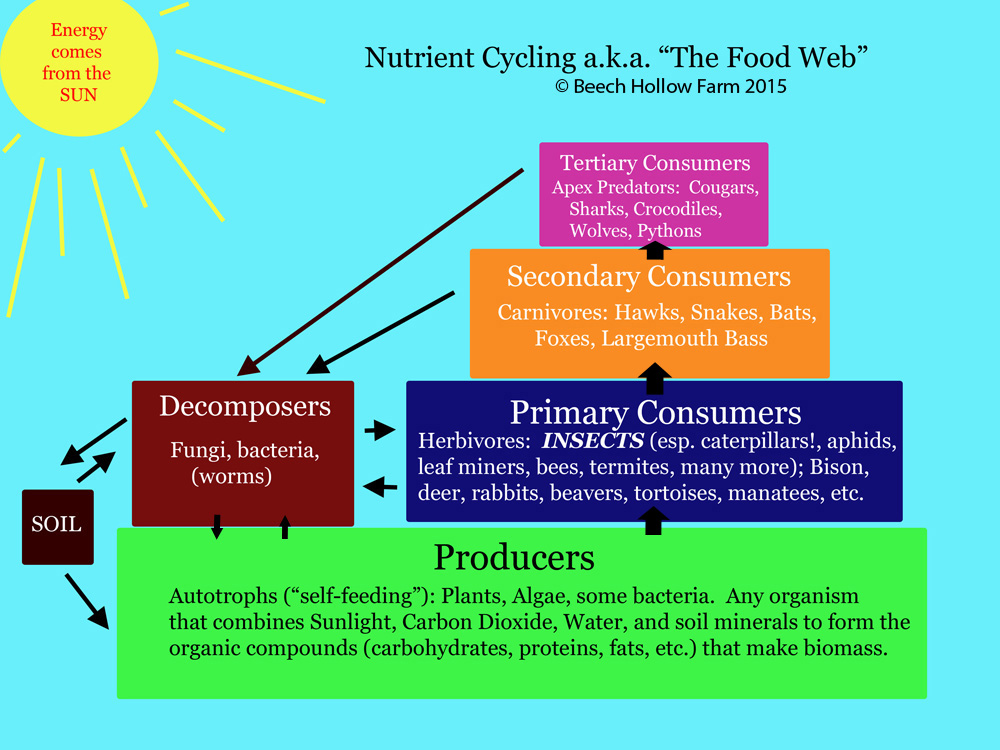

(There should be more arrows going all over the place, a ‘web’ if you will, but like I said, this is simplified to highlight the cyclical nature of the whole process.)

The main points of this graphic I want to focus on are 1) Energy comes from the sun. 2) That energy is harnessed and stored as carbohydrates by plants. 3) The rest of the system depends upon harvesting that stored energy. Everything else is standing on that foundation of plants

As omnivores, humans have the ability to derive our energy from many sources, and in fact need a varied diet to acquire all of the nutrients necessary for our bodies to function. It allows us to occupy nearly any area on the planet, but other creatures are not so easily adaptable to new foods and environments. Survival strategies are often dependent on the seasonal abundance of plant resources with periods of migration or hibernation to cope with food scarcity. Many insects have evolved to become specialists at feeding on certain types of plants in response to the annual growth cycles in temperate climates. Typically, an egg is laid on or in a preferred food source, a larva emerges and feeds on that food source until it consumes enough energy to pupate into a winged adult. The adult then flies off to find a mate, locate another larval food source, lay egg(s), and repeat, if possible, until they die. Aphids, Wasps, Bees, Moths, Butterflies, Flies, and Beetles all follow this same basic life cycle.

Butterflies and Moths, collectively known as Lepidoptera, have adapted specialized strategies to feed on plants and mitigate the effects of their defenses in an evolutionary tango over the past 60-100 million years. Through the process of evolution and adaptation the insect’s fate has been inextricably tied to the fate of the plants they consume. Lepidopteran larvae, commonly referred to as: caterpillars, grubs, tentworms, silkworms, inchworms, armyworms, etc. are a crucial first step in transferring the sun’s energy throughout the ecosystem. A feature of their specialized feeding behavior is that they have become much more efficient at converting the plant material into proteins with which they build their bodies. Those proteins are the main food source for many of the creatures that occupy the next trophic level up the pyramid.

One of my favorite sources for information on butterflies, moths and caterpillars is BAMONA (Butterflies and Moths of North America), a website/database operated by the Butterfly and Moth Information Network. It has tons of information and resources for anyone looking to learn more or contribute their knowledge and sightings of Lepidopterans. I spent a little while browsing their database of species and compiled the following list of common names for Butterflies and Moths. See if you can spot the pattern:

“Elder Shoot Borer Moth, Maple Leaftier, Small Aspen Leaftier Moth, Black-headed Birch Leaffolder Moth, Oak Leaftier Moth, Poplar Carpenterworm Moth, Birch Tubemaker Moth, Pecan Leaf Casebearer Moth, Alder Tubemaker Moth, Birch Dagger Moth, Cottonwood Dagger Moth, Tupelo Leaffolder, Fringe-Tree Sallow, Knapweed Root-borer Moth, Poison Hemlock Moth, Virginia Creeper Borer Moth, Fall Clematis Clearwing Borer, Seagrape Spanworm Moth, Walnut sphinx, Poplar Catkin Moth, Yellow Birch Leaffolder Moth, Consular oakworm moth, Oslar’s oakworm moth, Peigler’s oakworm moth, Orange-tipped oakworm moth, Spiny oakworm moth, Pink-striped oakworm moth, Orange-striped oakworm moth, Chestnut Crescent, Live Oak Antiblemma, Oblong Sedge Borer Moth, Large Boxelder Leafroller Moth, Spring Spruce Needle Moth, Fall Spruce Needle Moth, Cherry Shoot Borer, Hickory Leafroller Moth, Hackberry Emperor, Ten-spotted Honeysuckle Moth, Wavy Chestnut Moth”

(These are just a sampling of the species whose Latin names begin with the letter ‘A’!)

The pattern to which I was referring is that the plant that the larva feeds upon is right there in the adult’s name. Many even tell you the plant part they consume: Leafroller, Shoot Borer, Root Borer, Poplar Catkin, Spruce Needle, etc. Being a specialist at consuming such specific plants and plant parts confers the advantage of less competition for food resources, but it is a double edged sword. If that particular plant or part of the plant is not available then the caterpillars cannot survive. This is where you, the human, enter the picture. Many of the native plants that were interwoven into the landscape and served their purpose as a larval food source for millennia have been marginalized or removed altogether. First, agriculture, next urbanization and development, and then landscapers all took turns removing the native smorgasbord and replacing it with foreign, undigestible plants. Whereas a human might view a Chinese Cherry tree ringed with a border of Monkeygrass surrounded by a freshly mown lawn as a tidy, beautiful landscape, a butterfly looking for a place to feed and nurture her young might see a desert or a wasteland devoid of food. That same human would probably derive a very similar aesthetic pleasure from an American Cherry Tree ringed with sedges and surrounded by native bunchgrasses, and over 500 species of Lepidoptera would see food and a nursery for the next generation.

Spring is nearly upon us. That time of year when everyone briefly turns their attention to beautifying their yards before it gets too hot. Beware the big box stores and their clone armies of gold medal winning plants injected with systemic insecticides. “Pest Free” is another way of saying “Useless to Wildlife.” Resist the impulse buy in the garden center. Do your research and find some plants that will satisfy your aesthetic wants AND wildlife nutritional needs.

Postscript:

In the course of researching moths for this article I stumbled upon an account of a moth with a truly unique larval food source: The Gopher Tortoise Moth (Ceratophaga vicinella). Based on the naming conventions described above what would you guess that Gopher Tortoise Moth caterpillars eat? If you guessed Gopher Tortoise Shells you would be correct! More specifically they consume the solid keratin that binds the many plates of a gopher tortoise shell together. Keratin is the same protein found in your hair and fingernails and other natural fibers such as wool. The ability to digest and derive sustenance from keratin is shared by a close cousin of the Gopher Tortoise Moth: the common Clothes Moth that loves to eat (you guessed it!) wool clothing and rugs. The amazing part of this relationship to me is that there used to be such a surplus of Gopher Tortoise shells laying around that their abundance encouraged an entire new species to branch off and specialize in consuming only tortoise shell keratin. Sadly, this strategy has proven to be risky with the decline of Gopher Tortoises, which is a direct result of the decline of the Longleaf Pine-Wiregrass ecosystem (and its seasonal fires) on which they are dependent. There are hundreds of other animals and insects that depend on Gopher Tortoises and their burrows in some form to survive, and none of them are doing well. Bring back the Longleaf!